This article uses Jeffrey K. Liker’s book, The Toyota Way.

Aviv was the owner and CEO of a company, and led marketing and business development.

Most sales and growth were in overseas markets, and Aviv personally managed activity in key countries.

He spent a lot of time on marketing trips and knew all the overseas clients and distributors.

He had an exceptional understanding of the global market, and his company grew. Aviv realized that one of the principles which will enable his company to continue to grow sales is quick supply and meeting promised deadlines.

He wanted to ensure that even when he’s away, the factory still supplied orders quickly, and in order to guarantee that, had large stocks of finished products, and always had merchandise in production.

All of my attempts to convince him to considerably reduce stocks and make the production process more efficient, fell on deaf ears.

Aviv always told me “quick supply is the most important thing and I don’t want to take risks”.

Large Stocks Hid Inefficiency and Faults in Production

Until one day, following complaints from several customers, the quality assurance supervisor ordered a full examination of the stock.

It revealed that the company’s warehouse held thousands of faulty products. The quality problem about which customers were complaining was caused by a fundamental problem in the manufacturing process.

This was the first crack in Aviv’s view, and he agreed to examine and change the manufacturing process.

Together with employees, and using the company’s data system, we identified bottlenecks in the manufacturing process, and the “boulders” which interrupted flow.

Over the years, the company invested a lot in advanced machinery, but in the department which we identified as the bottleneck, work was still manual and inefficient. Even the computers they were using were the oldest in the company, worked slowly, and held up production.

Some of the machinery was domestic, not industrial. A remnant of a time when the company was new, the manufacturing process was still developing, and they’d improvised experimental measures.

Additionally, without managerial oversight, the “how-to”s of the process were being passed from one employee to another verbally. Whenever an employee would leave, and a new one hired, a piece of professional knowledge was lost.

In a joint effort, we worked with management and with that department’s employees, to “shake up” the manufacturing process, the company invested in automation, and the little “bottleneck” department was given special attention.

We saw a great improvement, but still not “continuous flow”.

Create Continuous Flow in Order to Raise Problems to the Surface

In Jeffery K. Liker's book, The Toyota Way, he presents Toyota's 14 principles, the second of which is: "create continuous flow to raise problems to the surface."

Some of the book's "how not to" examples seem taken straight from Aviv's company. But in fact they're from many companies that implemented Toyota's production system (TPS) - known also as Lean Production.

The main reason many companies work this way is because, intuitively, we tend to think that large scale production and maintaining stocks will ensure efficiency. A so called "size advantage".

But reality is different. The above example, from Aviv's company, is only one aspect of the problem caused by working with over production and large stocks.

Think of the stock taking up valuable space in your warehouse and on the production floor.

Of the mess caused by finished products stored on the production floor, even causing a health hazard.

Think of the products, materials, and packaging you've had to destroy.

Or of the dead stock lying in warehouse, which you're too afraid to destroy, lest it affect the company's bottom line.

Producing large batches and large stocks means a longer gap between the time you pay for materials and labor, and sale of the finished products.

In other words, a larger working capital and a considerable damage to the cash flow.

What is Continuous Flow?

Liker writes that when Toyota's factory was first set up, it followed the organization of the Ford factories. But they couldn't compete with Ford's quantities and size advantage. So they optimized materials flow in the factory, so that it moves faster. The best way to do that was to reorganize the factory by product, instead of by process.

According to lean thinking, the best portion size is always the same - 1. Even if you can’t always achieve the ideal size, you should aim for the smallest number, and situate the required stock strategically.

Liker adds that flow is at the heart of lean production: it shortens the time between raw materials and finished products, leading to better quality, lower costs, and shorter supply times. Less stock also reveals hidden problems in the process and forces you to address them.

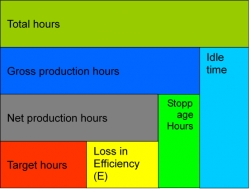

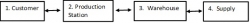

Continuous flow requires that each station only supply its “product” when the “client” (the next station) calls for it. This production pace is called Takt Time - the rate of demand, or of purchasing.

Working with Production Cells

Traditionally, you’d organize machines by type, produce an amount, and move it to the next department, where there’s another type of machine.

In continuous production you organize the production floor in cells according to the complete process - with each “cell” made up of one machine of each type. The machines are set up in an L or U shape - so that once one phase of production is complete, the item moves immediately to the next one. This eliminates the need for stock lying around, and no machine produces unless the next machine in line requires it.

In this method, each employee operates more than one machine.

Moving from the traditional method, with each employee operating only one machine, to continuous production, with each employee operating multiple machines, can be met with resistance.

Any change can be perceived as a threat. Be patient, and explain the reasoning behind the change to all employees.

Muda

In 2018, I discussed Toyota’s seven hotbeds of waste (Hotbeds of Waste: Where We Lose Major Money without Noticing). Liker adds an eighth:

- Excess production.

- Wait/idle time.

- Excess transportation.

- Over working or mishandling.

- Excess stock.

- Excess movement.

- Faults.

- Not using employee creativity.

Liker’s addition is very interesting, and I’ll discuss it shortly.

Advantages of Continuous Flow

Continuous flow production has several considerable advantages over traditional production.

- Quality. Continuous flow makes it easier to build quality. Every operator is a supervisor, and tries to correct mistakes in their station before they’re passed onwards.

- True flexibility. When we only produce what’s required, and not excess stock - production times are shorter and new orders are processed faster.

- Higher productivity. Think how much time and resources are lost when you produce excess stock. Stock that then needs to be stored. How much time is wasted keeping track of parts and faults, or fixing products?

- Frees up room on the production floor. Parts move from machine to machine, all of which are in close proximity to each other. There’s no stock stored between machines, and no delays as parts are moved between departments. Everything is close by.

- Improved safety. One reason for this is the lack of forklifts required. Small batches mean you don’t need large forklifts. Small carts are enough.

Another reason for improved safety is organization and order. Continuous flow decreases, or even eliminates, production floor stocks. This leads to more open space and more order and organization, which in turn considerably improve safety conditions. - Improved morale. Working with continuous flow reveals the underlying problems in your process. Every problem with the product or the equipment halts production (since there’s no excess stock and parts are only produced as needed). This then creates pressure to resolve the problem quickly. Employees from the station experiencing problems, as well as from nearby stations, work to find a solution, using their creativity and experience. The impact production employees have on problem solving makes their work more meaningful, and improves their motivation. The ultimate advantage of the continuous flow method is that it challenges all employees to think and improve.

Note: in the book The Toyota Way, and probably in Toyota itself, it’s taken for granted that when problems occur in production, all employees will take part in solving them creatively. This isn’t the case in many companies. Too many managers don’t believe in their employees, and don’t expect or allow them to take part in brainstorming solutions. Not even when dealing with problems in the production line, with which they are intimately familiar.

Mostly, managers don’t listen to what their employees have to say.

Why Is It Difficult to Create Continuous Flow?

The biggest difficulty is our fear of change. A fear shared by both managers and employees.

Additionally, there could be resistance if employees feel a change is being forced on them.

The biggest change is operating several machines in a production cell, instead of just one machine.

Such resistance, stemming from fear of change, should be addressed patiently.

This difficulty will pass with time. New employees will join the team, and continuous flow will be the reality they know.

Taiichi Ohno has described the resistance he met when he implemented changes in Toyota, and how he dealt with it. Even though he was a young engineer and impatient to progress with his changes, he saw that he needed to move slowly and patiently.

Your Suppliers

A sore spot and an obstacle on the road to continuous flow is being dependent on your suppliers.

Liker writes that Toyota only works with suppliers who embrace their method and deliver orders as agreed upon.

In more localized industries this can be an especially painful problem due to the lack of commitment from many companies.

But, just like you look at suppliers’ prices and quality, you should also consider delivery times when choosing a supplier.

A large Israeli company fines late suppliers heavily, and companies that want to work with them must toe the line.

In the automotive international industry it is also common practice, and suppliers deliver exactly on time.

In other words, it’s possible. You only need to pick the right supplier.

On the other hand, one of the largest retailers in Israel is in the habit of giving suppliers projected dates, changing them constantly, and marking everything “urgent”.

Companies that want to work with them are forced to keep large stocks of completed products, materials, and stocks on the production floor.

I doubt supplying to that large company adds something to ultimate profits. I’ve met suppliers that understood that and stopped working with them.

Delivering on time has been discussed extensively on this blog, and you can read an important article on the subject here.

Summary and Recommendations

Traditional and so-called intuitive thinking focuses on quantity. Bigger manufacturing series and large stocks will lead to efficiency.

But as I show above, the opposite is true: amassing stock leads to less efficiency, increased costs, lower quality, and long supply times.

Contrastingly, continuous flow production, following Toyota’s second principle, increases efficiency, shortens supply times, improves quality, and engages and motivates employees.

At the base of continuous flow are a few principles:

- Each station only produces what the next station needs, when it needs it.

- No stocks.

- Working in production cells organized according to the manufacturing process. Or, not grouping machines by type, but in clusters of all types, with each machine next to the one used after it in the process.

- Each employee operates several machines.

- When a machine, or a station, suffers a problem, the line stops and all employees take part in brainstorming and implementing solutions.

In continuous flow, you meet and deal with challenges on a regular basis.

These challenges also exist when you produce in large quantities, but large stocks on the floor and in storage mask the problems and prevent solutions.

I recommend you work with continuous flow.

Focused and Fast Coaching and Consulting Services for CEOs and Companies during the

Coronavirus Crisis

The Business Excellence team can help you build, within 2-4 working days, a plan to survive this financial crisis, or to achieve your goals, as we’ve explained in our first webinar from August 2020 [in Hebrew].

Our experts have a wide and diverse experience of over 100 years combined managing companies and consulting to CEOs – so we will be able to identify the unique needs of each company, and find the safest and fastest way for you to approach the new challenges presented by the crisis, and to ensure your company’s resilience.

If you are interested in my professional help, personally or for your company, the best way to contact me is to send a request through the Get in Touch form here.

My First Book: Manage! Best Value Practices for Effective Management

My First Book: Manage! Best Value Practices for Effective Management