Dalia is leader of a large-scale efficiency project at a major communications company. To her astonishment, she related to me, project managers were proud of being only 20 or 30 days late in delivery. In other words, from their point of view, the delay in delivery, never mind their commitment, had already become a norm.

Now let's try being "late by only a month".

Interestingly enough, not maintaining one's commitment to delivery times is prevalent amongst almost all industries in Israel, whatever field they may be in.

One CEO once told me he often gives advance commitment for unrealistic delivery times he has no possibility of reaching. But if he doesn't commit to brief delivery times, he won't get the order.

A delay in delivery provokes pressure from customers, resulting more than once in salespeople wandering around the production floor, making sure the orders from their customers get into production, and then the party begins. Project managers and production managers are helpless and unable to defuse the situation.

"If we could only produce more…"

Efficiency and Increase in Productivity

I will address project management separately, at another time, and will devote this article to the production floor.

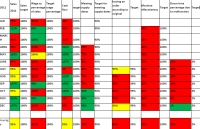

The best way to attain an improvement in efficiency on the production line (and from here, the possibility of also increasing productivity and reducing costs), is to measure the efficiency of the production machine or line, to analyze the different types of loss in time or yield and to develop actions for improvement.

Although the first reaction I always get is objection, the best way to measure the efficiency in which we have worked in a 24-hour period (or a week, month, etc.), would be to compare the yield of good units of manufacture to a potential, theoretical yield, if the line were to run continuously, with no stoppages at all, no problems or switching of product, and at the highest theoretical speed permitted, according to the manufacturer's or company engineer's definition.

Of course, we'll never reach 100% efficiency, and we don't intend to get there. Instead, we measure ourselves in comparison with an absolute, set value.

This kind of measure, of good units we have manufactured in a set period of time, is not dependent on any subjective listings by the workers, errors in measurements, etc.

But in order to analyze the results and improve, we will first need to characterize the losses in time or yield.

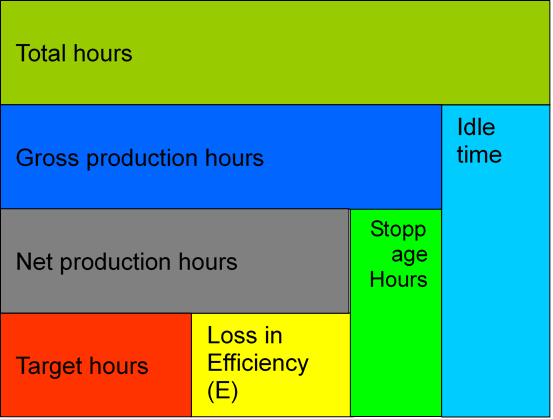

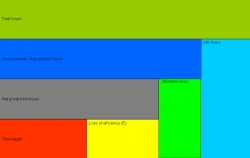

Let's take a look at the illustrations below:

OEE Measure

The relevant measure for our task is known as the Overall Equipment Effectiveness measure. First, let's consider some potential situations with our production lines.

The line can either produce or not produce.

First, let's define the types of stoppages or losses in yield and afterwards we can look at the distribution of production hours.

When a line is not manufacturing, there are three possible reasons for it:

- The line is not planned for production. We call this "idle time". For example, stoppages by law (Shabbat, in Israel), or no orders.

- The line is not manufacturing, but there are planned activities on the line, like preventative maintenance or set-up. We'll call this "stoppage time".

- The line is set up for production but is not manufacturing. For example, lack of raw materials, missing employees, technical fault, or loss of yield due to quality problems, reprocessing or reduced speeds. We'll call this "loss in efficiency".

Now let's define times.

- Gross time is the entire number of hours we could possibly manufacture.

- Net time is all of the hours we have listed for planned production.

- Target time is the number of hours it would have taken to manufacture what we did, if we had operated at the theoretical speed. The discrepancy between net hours and target hours is our loss in efficiency.

For example:

The line was planned for 20 hours of manufacture, with no planned stoppages. Actual yield was 6,000 bags and the theoretical speed was 500 bags per hour. Meaning, theoretically, we could have manufactured the 6,000 bags in 12 hours. But we planned for 20 hours of manufacture.

So, we have a loss in efficiency of 8 hours, or 40%. And by the way, these numbers are very realistic (before we improved).

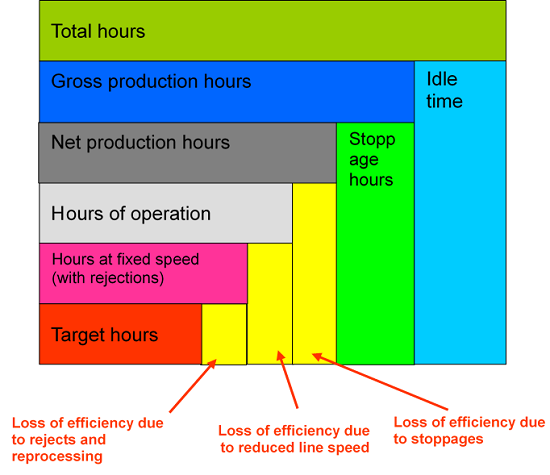

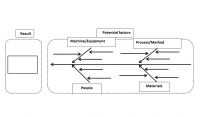

We can divide up the loss in efficiency into three categories.

Let's look at the next illustration:

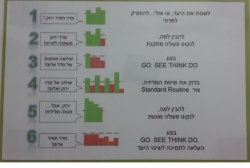

How do we give priority to actions for efficiency?

Over the years, we have learned that rather than relating to loss of efficiency in percentages, we should define it in product units.

Every week at a chemical plant, we listed a loss in yield of tens or hundreds of tons of product. At other companies, we defined their loss in productivity for solar mirrors, or chip bags or any other product they made.

In all of the cases, illustrating the situation in the above manner made it clear to everyone and generated a very high motivation at all levels to improve.

The measurement's weak points

Working this way requires several actions and new definitions, which generate the preliminary objections:

- Definition of the bottleneck on the line.

- Definition of the theoretical yield for each product.

- An accurate and reliable listing in the line's activity log.

- Introducing a routine of uploading the data into an Excel file.

- Analysis of results with an improvement team of employees.

Summary

In every case where we've worked in this manner (whether I was production manager at a major plant, or CEO, or in my present position guiding improvement processes), the improvement was startling.

Not only that, the shared involvement in measurements on the production line and the analysis by an improvement team of employees resulted in the introduction of innovative and original ideas for improvement.

My First Book: Manage! Best Value Practices for Effective Management

My First Book: Manage! Best Value Practices for Effective Management