In this article I refer to two books: Dan Ariely's "Payoff: The Hidden Logic That Shapes Our Motivations", and Itzhak Kantor's "The Story of Plasson".

When Kibbutz Shamir founded Shalag, the technicians from the company which manufactured the production machinery said they've never met a team which understand operations so quickly and achieved so much so quickly.

The secret was, the Shalag team was made of Kibbutz Shamir members who felt the factory was theirs. They were a select team who set themselves a mission, to start a new industry in the kibbutz. They felt deeply connected to the fledgling industry.

The founding team members were all fully informed, hierarchy was ambiguous, salaries were equal, and of course there were no bonuses.

The entire kibbutz supported the factory's founding, and the team was the lead. It was part an integral part of the kibbutz's life. Management was on a rotating basis, and everybody met as equals in the dining hall, in kibbutz meetings, during scheduled chores and guard duty.

Broadly speaking, we can say every employee felt the success of the new factory – was dependent on him personally. Each one, regardless of his specific role, looked at the big picture. No one felt like a cog in a machine, knowing only his specific role, without a clue as to the company's wider goals. Everybody felt meaningful and motivated.

The other side of a kibbutz's involvement in industry appears in another one of my memories.

This was a few years before I became the CEO of Shamir Optical Industry. The kibbutz assembly needed to approve participation of a team from the company in a professional conference in Italy. I remember a heated debate. Travelling abroad was rare, and every trip was a cause for envy. In the assembly, a suggestion was raised – instead of one of the executives, "Sarah", a kibbutz member, will go, because she hadn’t been abroad yet.

Professional and business considerations, whether or not "Sarah" spoke English or another European language, whether she knew the company's clients, or will assist in gaining new ones, whether she'll be able to represent the company at the conference – weren’t even discussed. The kibbutz members weren’t familiar with the conference, nor with any knowledge "Sarah" might need while standing in the booth there. And they didn’t care at all.

I don’t remember discussions of strategies or long term plans (if there were, excellent), but there certainly were heated discussions of business travel abroad and issues relating to daily business decisions. Decisions which often carried a hefty price tag.

The Dialogue between Employee-Investment and the Whole Kibbutz Being Involved in Business Decisions

Itzhak Kantor, who led Plasson for 26 years, from founding to success, described in his book, "The Story of Plasson", the space between the engagement, involvement, and commitment of the kibbutz members who worked at Plasson and the involvement of the kibbutz assembly in business decisions.

On the one hand, a deep connection to the company, motivation, and meaningful work

Kantor describes how before the company shipped its first international delivery, production wasn’t complete, and the last date for loading the shipment on the boat was about to be missed. They were determined never to have delays in shipping, so the kibbutz members worked over the weekend to complete the work. They were successful, and the client got their shipment on time.

Salaries for kibbutz members working at the factory were (and still are) equal, without bonuses or stocks. Members, and later outside employees, were fully informed on the company's activity in Israel and abroad. They felt a strong sense of belonging and identified with the company. In Plasson everybody knew the big picture, and knew how their specific role influenced the final product and the company's success. Kantor relates how he always made sure to give full reports to the kibbutz as to what was going on with the company.

Even though Kantor headed the company for years (part of them as a joint CEO) he stayed on the kibbutz's chore roster, and participated in the kibbutz's social life. This greatly contributed to an ambiguity of hierarchy and the employees' sense of connection with the company.

I assume any kibbutz members reading the above don’t understand why I highlight these characteristics. It's like writing that the sun raises in the morning. But try to imagine the CEO of a large company, or a bank, taking their turn cleaning the toilets, or washing the dishes in the dining hall.

These simple things are part of the important factors which make the difference between employees' alienation and their investment and engagement in company goals.

The Benefit

Employees who identify with the company, who are engaged and who feel they do meaningful work, are highly motivated. Generally speaking (and while there are, of course, exceptions) we can say that all of Plasson's employees wanted the company to succeed and all were highly motivated.

I'll jump ahead, and write that when I visited large Japanese companies in the past, upon entry everybody changed into identical robes and shoes. On the production floor, employees and managers all looked the same. Like in the kibbutz, Japanese companies reduced in this way employees' alienation and promoted a sense of connection.

The principles and reality described above created an advantage for industries in kibbutzs.

On The Other Hand, Everyone's a Stakeholder and Has an Opinion. On Everything

Kantor shows the involvement of the kibbutz's assembly in business decisions: Plasson's investment plan was discussed as part of the kibbutz general plan, alongside investment in the youth center and in agriculture. Additionally, the principle that no "hired work" (that is, people not from the kibbutz) could be employed won over any business logic.

One of his examples describes how, after bitter arguments, the kibbutz assembly didn’t approve a partnership with an Italian company in a European marketing firm. He reports that for some, a partnership with "a capitalist" was horrifying.

Throwing Out the Baby with the Bathwater

Kantor further writes how it took years for the kibbutz to understand that their company engaged in "capitalist production" not only when it came to production and marketing, but also the tension between a socialist society and an industry whose rules are a result of inequality, competition, and a drive for excellence.

I know cases of kibbutz members (in other industries) who called board members late at night to pressure them about business decisions, for non-business related reasons.

The involvement of kibbutz members in daily operations and decision making, while led by non-business related considerations, has caused problems in the industry, leading even to a stand-still. Here I mean daily and tactical decisions, not strategic or long term discussions and reports on goals, achievements and results – as discussed above.

Based on my experience with industries in kibbutzs, I can say that only in those cases when business activities and considerations were kept separate from the kibbutz, has success been achieved.

But with this necessary separation, many of the important values which promoted employee engagement, connection, information sharing, and meaningful involvement have been left behind.

In this manner, industries in kibbutzs (that I know of) have joined general trends in industry and lost one of their important advantages.

Old Kibbutz Values Have Been Revived in Leading Global Companies

In fact, the term "revived" isn’t accurate, because these values (which I'll discuss below) are created separately from a kibbutz too.

This time I focus on these values' importance in creating motivation, engagement, and investment in company goals, using the book "Payoff: The Hidden Logic That Shapes Our Motivations", by Prof. Dan Ariely.

These values can be found in many leading global companies, and are used to achieve better results, promote employee engagement, and produce better products more efficiently. I've personally come across them in several companies, and read about others.

One of the important goals working with these values is to retain good employees. Ones who identify with the company and feel meaningful, and so won't be quick to leave.

Work as Barter – Labor for Money

Dan Ariely writes that the rate of unmotivated employees in the US grows every year, and at the time of writing his book it was, according to the Gallup Institute, over 50%. Only 17% reported active commitment.

According to Ariely, one of the reasons is the perception of the job market as a place where individuals supply labor in exchange for money. Following this perception, as long as employees are getting payed they won't care even if their work lacks meaning. Because the payoff is so important, employees are willing to suffer for it.

Ariely writes that this perception originated in Adam Smith's 1776 book "The Wealth of Nations", where he described the benefit of dividing a task into its components, and assigning each one to a different person – which greatly improves efficiency.

Ariely is amazed that such ideas can survive even when it's made clear that they're no longer relevant. Smith's Industrial Age perception was accepted by later generations as an indisputable truth, even when our personal experience, as well as scholarly research, show that work is more than just getting money to buy things.

On the Importance of Meaningful Work and Employee Engagement

Ariely writes that offering employees opportunities for meaningful work and engagement increases their diligence and loyalty.

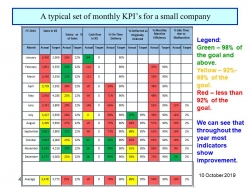

I see it again and again in companies where my team and I begin working with improvement teams. Aside from the immediate contribution to the company from getting previously unknown information from employees, they themselves become more meaningful. Suddenly their opinions matter. Within a short time, you can see a new light in their eyes, and a new energy is felt on the production floor.

In one company, the operations VP pressured the CEO to allow new work methods, including improvement teams. Eventually the CEO "gave in", with a condition. He agreed to a trial period, and said he'll look at the financial results.

After several weeks of working with improvement teams, the CEO told us he feels a new energy on the floor. He recognized levels of motivation he didn’t see before, and said: "forget about the money. The financial result will come, I'm sure. What I'm seeing right now is excellent."

In the past, when I was the CEO of a large Osem-Nestle factory, we began working with improvement teams. The first one included a very charismatic but very negative employee. In her eyes, everything was bad. She saw the negative in everything we did. Shortly after the improvement team began working, she changed completely, and used her charisma to lead other employees to good places.

I used to bring her up as an example in management meetings, and we continued to have her take part in improvement teams from time to time. After a year she recognized her transformation herself, and told me: "you know, Ze'ev, I think all employees should take part in improvement teams."

This truth is easy to test, for example after management changes in a company, or a sports team. The new manager, or coach, sees a talent in a player or employee who didn’t stand out before, and who suddenly becomes a highly motivated and central player. Or the other way around, of course.

I go back to the examples from above, of kibbutz members who worked in factories (or other places) and were very motivated and felt a deep connection to their workplace. They felt meaningful, because their opinions mattered, they were listened to. Especially when they were part of the founding team.

Ariely presents in his book an experiment which shows how our intuition downplays the importance of meaningful work. So even though in reality meaning increases motivation, when looking from the outside in we tend to think differently.

Who's Responsible? Employees or Management?

I met recently with the CEO and owner of a small company struggling with quality and efficiency problems as a result of low employee motivation. The meeting also included the co-owner/VP, and an advisor.

The three of us tried to convince the CEO of the connection between the employees' lack of commitment and motivation, and the company's bad results. The CEO wasn’t convinced and kept saying "I'm paying them, I want them to work". It so happened that Ariely's book was in my bag, and I quoted the relevant information from it. The CEO listened, but rejected my argument and stuck to his opinion.

I think the perception of work as barter – is also the result of wanting to blame employees, instead of management, for their lack of motivation.

If in the work place, two sides exchange labor for money, and low motivation harms quality and efficiency – than it's the employees' "fault". Management payed them, but they don't give their labor.

Contrastingly, when management knows to offer employees opportunities for meaningful work and engagement –they'll be motivated and quality and efficiency will improve – management will be responsible. It's management that is required to initiate further actions, not just pay salaries.

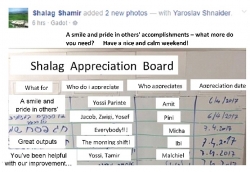

Appreciation

The importance of employee appreciation has been discussed on this blog several times (see here, and further links at the end of this article).

In his book, Ariely discusses several lab experiments which have shown the importance of appreciation, and writes that he looked for an opportunity to conduct such an experiment in the field.

The opportunity came at Intel's chip manufacturing factory. In that factory, bonuses were given for increased production.

For the experiment employees were divided into four groups:

The first group was promised a monetary bonus if they manufactured the required amount or more.

The second group was promised a free pizza for the above.

The third, an appreciative letter from their manager.

And the fourth group, the control group, wasn't promised anything.

Over four work days, the group which was only promised compliments had the highest production rate, while the group which was promised a monetary bonus had the lowest.

Summary and Recommendations

In this article I showed how engaging employees with company goals, sharing information, promoting a sense of meaning in one's work, ambiguous hierarchies, and appreciation all contribute to employee motivation. These values also help retain good employees and bring about improvements in quality and efficiency.

These values were once part of industries in kibbutz, and were largely abandoned when the necessary separation between the kibbutz and the management of the business was established.

But they also developed and can be seen today in leading global companies.

If you are interested in working with me or with my team, to improve the management of production materials, personally or for your company, the best way to contact me is to send a request through the Get in Touch form here.

Links

My First Book: Manage! Best Value Practices for Effective Management

My First Book: Manage! Best Value Practices for Effective Management