Aviv set up a company and supervised production and sales in the local market from day one. Unlike many other founding CEO's, Aviv understood that if he wished to grow, he would have to let go, to bring in managers and give them responsibilities.

Aviv also appointed QA and HR managers in the early stages, which is rare. He truly understood the market and learned to recognize global trends. Thus, his company grew swiftly, entered new, innovative areas and succeeding in establishing a base overseas.

From many aspects, Aviv's company was a success story. But he had a weakness: he found it very difficult to rid himself of managers and employees who did not fulfill their responsibilities. Aware of this weakness, all his managers were hired following strict selection processes.

However, mistakes are sometimes made there too, and over the years, Aviv attracted managers, some of whom were not fit for their position. Aviv knew they were hindering the growth of the company, but he didn't have the courage to let them go or to move them on to other positions. He hoped they would leave by themselves, but they did not do so.

Aviv's strength lay in his ability to read the market and develop company business. He always told me that the moment he found someone suitable, he would appoint them as CEO and focus himself on business development.

Years went by, and Aviv did eventually find someone to take his place as CEO. In a short time, all of the unsuitable managers were replaced.

Making difficult decisions

As CEO, Aviv worked diligently towards his vision and made daring decisions in all related to company and product development. But at the same time, he suffered from a weakness shared by many CEO's: the ability to make difficult decisions on a personal level: to move managers to positions more suited to them, or to fire them.

CEO's who are also owners may permit themselves this weakness because there is nobody above them to fire these managers if the company fails. Only the bank account matters. But it turns out that a low bank account often isn't enough to push them into action.

My friend, Moshe Rubin, says that each morning he begins with the most daunting task, the most difficult one. Moshe is a very brave person, and not everyone can do what he does.

In the distant past, when I managed the branch of field crops on my kibbutz, I worked with a man named David, who was very talented and professional, and knew how to do all of the work in a most professional manner. But he would let me know what he had done, without taking instructions.

Instead of my managing him, he managed me. I was trapped. On the one hand, I didn't want to lose him, but on the other, he was jeopardizing our organizational discipline. Other workers learned from him and began to test my limits. This was a very important lesson to me, and it served me in positions I held in future.

The most difficult decisions are on a personal level

The most difficult decisions involve people, either when it's clear that a specific manager is not suited to his/her position or when they object to steps the CEO is leading, remain stubborn and stop them.

For example, at a major company, CEO Giora understood that a significant change was necessary in company performance, so he decided to implement Toyota's method, Lean Production.

Giora called in an external individual to help him with this task, and after a year of hard work, he understood that his operations manager objected to changes and would not permit implementation, and he had to stop the process.

Could Giora, the CEO, have acted otherwise? I would suggest taking the following path:

- Present company management with current results and clarify the need for change.

- In the next stage, suggest your solution to management (lean production). If it is accepted, set objectives and time schedules for realization of this process.

- If there are objections among management and an alternative solution is proposed, the CEO may either convince management to adopt his solution or take the proposed alternative and set objectives for improvement, with time schedules.

- In any case, the key is a plan of action for reaching objectives with time schedules and monitoring of the process.

- If the various managers (including the operations manager) do not maintain their objectives, they must either propose a plan to do so, or leave the company.

- In this example, objectives were not met and the CEO gave in to the operations manager instead of replacing him.

- If this company had been a subsidiary of an international company that wished to implement lean production and the implementation was being delayed, they would replace the CEO or the operations manager. It is more probable that the operations manager would recognize that behind the decision to implement lean production was an unequivocal determination and he/she would cooperate.

How to cope with managers that do not succeed in bringing in the required results

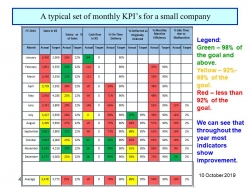

In the two examples I gave above (Aviv and Giora), there were VP's involved, or other managers that did not bring in the required results. It is much easier to work in the domain of measurable results.

Often, friendly relations with the CEO make it difficult to move the manager from his position, whether it be that same manager who is friends with the CEO, or a kibbutz member and a CEO who fears his power.

However, if the CEO defines objectives (as defined by company owner or board of directors) and his subordinate managers do not maintain them, the issue is simpler. Often the manager (or VP) understands that they are failing and leave, or intervention is required from the CEO.

The complications begin when there are objectives, the VP doesn't maintain them over time and the CEO enables the VP to continue in their position.

In this case, the CEO is derelict in his duty. In the example above, Aviv was aware of his weakness in firing managers that do not maintain their objectives, and as he is also company owner, he decided to bring in a CEO to act in his place.

work meetings

Yossi is CEO of a medium-sized company who asked for my advice on how to cope with Yaron, his production manager (and who reports to him directly). Yossi told me that Yaron ignored him and that all his attempts to initiate a one-on-one discussion had failed. I found out that Yossi's attempts comprised of asking Yaron to come into his office for a discussion.

Yossi realized something was bothering Yaron and creating tension between them, and thought that a private discussion might improve the situation. He was right, this type of discussion is important, but Yaron avoided the talk and did not come to Yossi's office.

I advised Yossi to set up a weekly work meeting with Yaron, at a set time and day of the week, and that he should arrange this through his secretary and not on his own. Yaron would not ignore an official summons to a meeting.

During the meeting, Yossi would work with Yaron on a work plan, on maintaining objectives, on coping with managerial problems that Yossi wishes to change in work processes, etc.

Work meetings are a wonderful tool for working with subordinate managers on maintaining their objectives, on different tasks and also in educating and helping them to reach objectives.

They also offer an opportunity for development of these managers who find it difficult to reach their objectives.

In addition, in these meetings, which should take place in the CEO's office and not in one of his manager's offices, you can cement the idea of who is boss and who reports to the boss. It may seem obvious, but it isn't always the case.

If, for example, Yaron allowed himself to ignore Yossi's attempts to initiate a discussion, in an official forum where the two are the only ones present and Yossi is the one who leads the discussion, his seniority is clear and unequivocal.

Coping with powerful employees

The central managerial difficulty lies in coping with subordinate managers – those who report to you – but there are also cases of CEO's having problems coping with powerful employees.

An employee gains power through his/her unique professional knowledge, membership in a workers' union, holding a key position, becoming friendly with the owners, or just plain having a strong personality. Whatever the case, sometimes employees may feel like they've got the company by the balls, and they exploit their power and don't work as they should.

I have seen employees sleeping at work, deciding themselves what tasks to perform or simply wandering around doing nothing on the production floor.

Their managers, who are not managing them, must consider two things: first, the employees are derelict in their work duties, hindering the company's ability to survive and may even bring about its closure. The second thing is fairness.

When all the employees are expected to work with clear rules of discipline and some employees enjoy a different status, they are actually taunting their superiors and a sense of unfairness develops.

When all the employees feel there is discrimination and unfairness, it decreases their motivation and desire to make an effort for the company (click here for an article I wrote a few months ago on the power of fairness in generating employee motivation).

Every time you refrain from coping with powerful employees or subordinate managers who fail the company – you are failing the company too.

What tools do we use to cope with powerful employees?

Employees who exploit their power or knowledge to squeeze the company or avoid working need to be handled with strength. Power vs. power.

Those who regularly read my blog may wonder at my saying this, but discipline is a cornerstone in the life of any company or organization. Without discipline, the tapestry that drives the company forward unravels. An employee who uses their power or knowledge to gain favors hampers group consolidation, group power.

No top team can win if its star players don't play together as a team (click here for an article I devoted to this subject three years ago, entitled: "Stars" and professional workers we can't do without).

Summary

In the current article, I have discussed CEO's or managers who are not coping with powerful subordinates and not managing them. Usually, they will come up with an explanation of why they're right and they have no choice. But this isn't true. They should remember that whenever they refrain from managing their people, it hurts the company and may cause it to close.

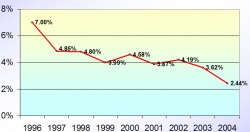

A year and a half ago, I published an article here entitled "Who is the manager here?". This has been one of the more popular articles in my blog, which has a readership of about 18,000 people. I guess this shows how much the subject of company management interests Internet surfers.

Next to this article, I published a survey where 25% of participants wrote that "the CEO of the company they worked at was an excellent one who encouraged all their subordinate managers to do their best, mostly by setting objectives and monitoring progress".

The survey results illustrate how much the employee public is aware and notices every managerial weakness, and how they relate to that.

I recommend that you take Moshe Rubin's suggestion. Every day, write down your most daunting task and begin the day with that task.

My First Book: Manage! Best Value Practices for Effective Management

My First Book: Manage! Best Value Practices for Effective Management